Over the last few years we have seen some maturation in the processes of providing information security assurance. This is good.

First let’s roll back into history, to the days in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, when it could not be safely assumed that the operating systems in use implemented access control correctly. “The Birth and Death of the Orange Book” by Steve Lipner, provides a wealth of detail on the situation in the U.S., in those pre-Common Criteria days. The Orange Book described several assurance cases, with C1 and C2 being deemed appropriate for commercial products. The rallying call back then was “C2 by 92!”

Realizing that a bunch of different national criteria was not a good way forward in the battle for cyber-security, and that reliance on commercially available products was increasingly important, the Common Criteria (CC) were developed and implemented, governed by an international Arrangement known as the Common Criteria Recognition Arrangement (CCRA).

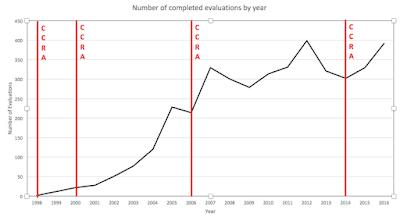

By my reckoning, the CCRA has been amended at least four times since it was established in 1998, with revisions in 2000, 2006, and 2014. Amendments were made that describe the agreed upon policies for use of the CC standards in the current situation.

This first chart shows the number of evaluations completed in each year of the CCRA.

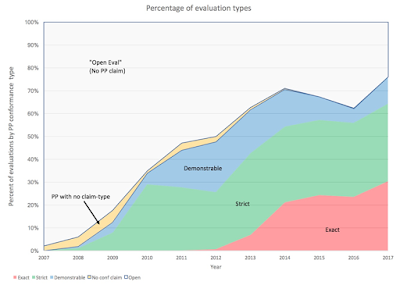

For the first version of CC, published in 1998, and in version 2, there was no concept of strict or demonstrable conformance.

This situation remained until CC version 3 was published in 2005. At that time three types of conformance were allowed: Exact, strict and demonstrable. As in earlier versions of the CC, partial conformance to a Protection Profile (PP) was not allowed.

Exact conformance is expected to be used by those PP authors with the most stringent requirements that are to be expressed in a single manner. This approach to PP specification will limit the ST able to claim conformance to the PP purely on the basis of the wording used in the PP, rather than a technical ability to meet the security requirements. This may be used in a Request For Quotation in a product acquisition process.

Strict conformance is expected to be used by those PP authors with vast experience of developing PPs, who again have requirements that must be adhered to in the manner specified. However, this completion permits the ST author claiming compliance to the PP to add to those requirements, provided it is in a restrictive manner. i.e. the additional requirements cannot weaken the existing requirements.

Demonstrable conformance allows a PP author to describe a common security problem to be solved and generic guidelines to the requirements necessary for its resolution, in the knowledge that there is likely to be more than some way of specifying a resolution.

By the time that CC version 3.1 was published in 2006, the notion of exact conformance had disappeared from the standard. So, this initial appearance of “Exact conformance” was with us for less than a year.

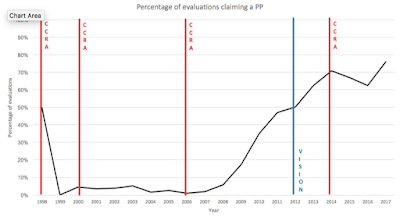

In 2012, a vision statement was published by the CC management committee. This introduced the idea of promoting the use of PPs, and evolved the PP development notion to include all stakeholders. (Previously most PPs were written by groups dominated by developers.)

Recently, in May 2017, proposed addenda to CC 3.1 R5 for exact conformance were published. This reflects the de-facto situation that exact conformance is specified in several PPs and in the cPPs defined in accordance with the CCRA of 2014.

This next chart shows the percentage of CC evaluations claiming conformance to a PP.

So, over the years the following types of PP conformance claims have existed.

- OPEN: An assurance claim (usually) on the Evaluation Assurance Level (EAL) scale is made, but the security functionality claimed by the TOE is open, no PP claims are made. Assurance consumers must be CC experts to navigate the claims. The specification of the ST is typically performed directly by the developer.

- NO CONF CLAIM: A PP is claimed but no statement in regard to the type of conformance to the PP is made. This is typically applicable to evaluations before CC version 3 was applicable.

- DEMONSTRABLE: A PP is claimed, as well as an assurance claim, but the security functionality claimed is variable. Assurance consumers must be expert to navigate any additional augmentation claims, understanding boundary restrictions, and also in understanding the rationale in regard to why something is equivalent to what was specified. The specification of the PP is typically developer led.

- STRICT: A PP is claimed; the security functionality includes a minimum set defined in the PP. Assurance consumers must be expert to navigate any additional augmentation claims, understanding boundary restrictions. The specification of the PP is typically developer led.

- EXACT: A PP is claimed that specifies the security functionality, as well as an appropriate assurance claim. The boundary of the evaluation is set. Assurance consumers can rely on a certification without much CC Expertise. The specification of the PP is typically led by the assurance consumer.

The following chart shows the percentage of each of these types of evaluation.

The chart shows that the evaluations performed in conformance with a PP have grown from less than 5% to over 70% over the last ten years. In 2012 when the vision statement was published the number of evaluations with a PP claim was around 50%, today we are approaching 75%.

Even though the notion of exact conformance has only just been formally published, some schemes have been promulgating exact conformance since 2011, and supported the development of PPs that specified this adaptation of strict conformance. These exact conformance evaluations now represent around 30% of the total evaluations performed.

The next life-stage for security criteria

There is much evidence that the CCRA has been a success, and continues to evolve to meet the needs of its stakeholders. Since the CCRA and the Common Criteria were established by nations who had already evolved security criteria (ITSEC, CTCPEC and TCSEC, aka the Orange Book), there has been a lot of change. With post cold war co-operation in the ‘90s, and greater reliance on commercial off the shelf products, the establishment of a device such as the CCRA was a great step forward. We should note that since then the reliance on COTS technology has increased and that the development of information technology has occurred over the last twenty years with exponential growth. This has brought new and more sophisticated threats to the table. The response to this proliferation of threats at national and regional levels is not completely uniform and is at varying levels of maturity.

For example, most nations have traditionally focused on the threats to government systems, with the original criteria and the Common Criteria standards developed by government agencies. Most nations now agree that the threats presented to their national infrastructures are critical in nature and must also be addressed, while the number of participants who have cybersecurity responsibilities are vast. A huge amount of effort has been focused on that in the last decade. Of course, this must go far beyond product evaluations, but these product evaluations are still a piece of the puzzle.

These “differences” have so far been accommodated using the deliberately flexible Common Criteria standards. A prime example being the emergence of the Senior Official Group-Information Security (SOG-IS) agreement, which addresses the European region’s directives and common goals.

The signatories to the CCRA have grown over the years, and today some twenty-eight nations subscribe to the Arrangement, with the latest participant being added in June (welcome to Ethiopia!) Truly, a recognition of the success of the Common Criteria in providing assurance in the security functionality of many ubiquitous IT products, is that it can be recognized by nations that do not have the resources of some others. However, the CCRA and its signatories are only part of the story. As nations develop cybersecurity strategies appropriate to their needs we observe some divergence in the application of the Common Criteria. To date, this divergence is reflected in the specification of the conformance-type to a PP, and the development of PPs applicable not just to technology type, but also addressing the needs of the various cybersecurity strategies.

The need for public-private collaboration has come to the fore, and the Common Criteria standards must develop appropriately. With this in minds, ISO will take a much greater role in the future development of the standards. The close liaison with the Common Criteria Development Board (CCDB) will continue, but ISO affords much greater opportunity for non CCRA nations and sectors outside the government-sector to be involved. The standards should allow all stakeholders, including those with differing use-cases for Common Criteria, to take an active role in their development.

For example, it may be appropriate that some sectors develop protection profiles that meet their own needs, perhaps set up their own “private” validation schemes, and even negotiate recognition arrangements appropriate to their sector.

In conclusion, the evaluation and testing of IT security products has evolved within the government sector over the last two decades, from the days of the Orange book, the number of evaluations performed each year has grown from a handful to over four hundred. We see differing use-cases for the standards, developing, not just within the government sector, but by other sectors, and we see different assurance needs for differing technologies. The next few years should be very interesting in terms of the development and use of the standards for product security evaluations and testing especially in keeping the standards flexible, finding the common denominators, enabling the needed use-cases and allowing for the development of meaningful mutual recognition.